16.01.2023

There have been some exciting announcements about the application of CRISPR-Cas9 type gene-editing technology to treat serious illnesses in the past few weeks. But this complex and rapidly evolving area of medicine raises some challenging IP issues.

Thank you

Recent gene-editing developments

In early December last year, Great Ormond Street hospital announced that it had used CRISPR base editing to treat a 13-year-old girl, Alyssa, with aggressive leukaemia. Following the treatment, she had no detectable cancer cells, and is in remission.

According to an article in the New Scientist, in order to overcome problems with conventional gene editing, a team led by Waseem Qasim of the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health “used a modified form of the CRISPR gene-editing protein that doesn’t cut DNA, but instead changes one DNA letter to another, a technique known as base editing” It added that Alyssa is the first person ever to be treated with base-edited CAR-T cells.

Across the Atlantic, in November researchers published clinical trial results showing how CRISPR gene editing can be used to alter immune cells to recognise mutated proteins specific to someone’s tumours. The results from 16 patients were presented at the recent Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer meeting in Boston, and published in Nature.

Meanwhile, researchers at the Institute of Structural Biology at the University Hospital Bonn and the Medical Faculty of the University of Bonn, also recently published research in Nature on CRISPR-activated protein scissors.

Other potential applications of CRISPR to have received recent attention include heart disease (“How gene editing could help solve the problem of poor cholesterol”), sickle cell disease, cancer and HIV.

CRISPR has huge potential for agriculture and it has even been speculated that it could help tackle climate change.

In a recent opinion article in the New York Times, Professor Fyodor Urnov of the University of California, Berkeley, argued that CRISPR could benefit millions of people with both rare and common diseases. “We must, and we can, build a world with CRISPR for all,” he wrote.

CRISPR explained

The potential of CRISPR has been understood for many years. Two of its pioneers, Professor Emmanuelle Charpentier and Professor Jennifer A Doudna, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020. The citation referred to their achievement in identifying that CRISPR, a natural anti-viral defence mechanism found in bacteria, could be programmed to cut any DNA molecule at a given point.

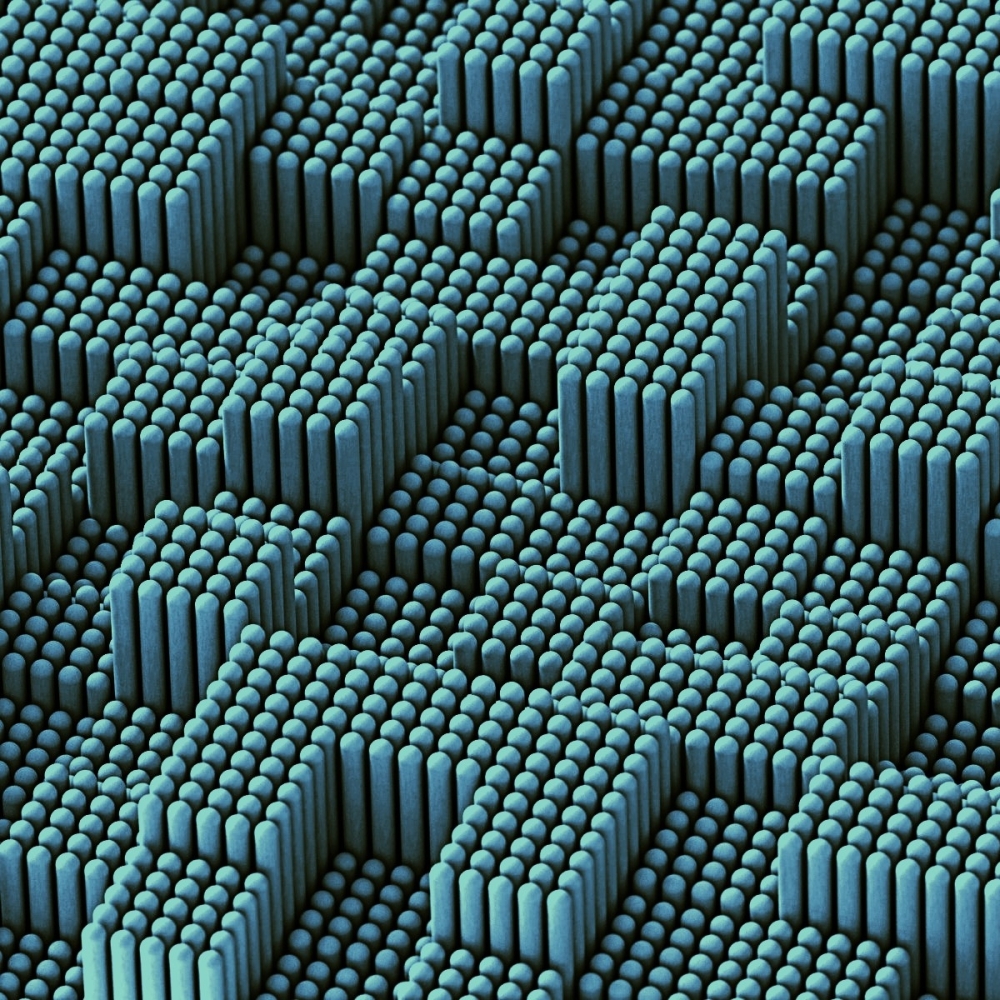

CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) refers to a naturally occurring collection of short, repeating nucleotide sequences found in many bacterial genomes. In response to a viral threat, the repeats are transcribed to RNA in the bacterial cell. The RNA forms a complex with a bacterial enzyme known as Cas (CRISPR-associated). The entire CRISPR-Cas complex is commonly referred to as CRISPR. Although there are many different types of Cas enzymes, most of our understanding of CRISPR is based on one specific Cas enzyme, Cas9, found in the organism Streptococcus pyogenes.

CRISPR’s potential to simplify gene editing has led to thousands of patents, research papers and clinical trials. Anyone wishing to work in this area needs to navigate a complex IP landscape.

Challenging IP issues

First of all, the sheer volume of patents makes it difficult to establish who owns which rights and what licence fees need to be paid. For example, IPStudies launched a CRISPR patent landscape analysis in 2014 and by December 2021 had categorised a total of more than 11,000 patent families and more than 270 licensing deals. It has recorded what it calls “a burst in CRISPR application patents, in particular from China, in all fields ranging from agriculture to therapeutics” and has also compiled a list of more than 100 variants of CRISPR enzymes beyond Cas9.

The number of researchers working in this area and the investment coming in will likely lead to even more patent applications being filed in the next few years. IP managers will need to ensure they are comprehensively monitoring the landscape in major jurisdictions, including the US, China and EPO, to ensure they have freedom to operate, and are able to take advantage of any patenting opportunities that arise.

A second problem is that ownership of key CRISPR-related patent rights remains in dispute. In multiple jurisdictions, there is a long-running and hard-fought battle between parties including, on one side, the University of California, Berkeley and, on the other side, The Broad Institute.

In Europe, multiple oppositions have been filed against many of the main CRISPR patents. The Broad Institute recently lost some of their key patents as a result of improper assignment of rights from one of the named inventors.

In the United States, interference cases are ongoing between the parties. In one case concerning a patent for the use of CRISPR-Case9 in eukaryotic cells, the USPTO’s PTAB ruled in February last year in favour of The Broad Institute, but the University of California has said it will appeal.

The chequered nature of the patent landscape means that licences may need to be negotiated with different parties in different jurisdictions.

The scale of the disputes has even led to some, including Broad, to call for a patent pool to facilitate licensing of CRISPR-Cas9 patents. One possibility is that this would be administered by MPEG LA, known for the MPEG-2 and other audio/video technology pools.

Why IP is critical

The promise of CRISPR is well understood, and it is fascinating to see some of the potential applications that are emerging. Delivering on this promise will depend in part on successfully navigating the complex IP landscape as well as the management of IP rights.

Attorneys at Keltie have particular expertise in CRISPR technology. We routinely advise clients working in this area on patent prosecution strategies as well as freedom to operate and licensing considerations.

Image from National Cancer Institute

08.01.2025

Patenting MetamaterialsMetamaterials - materials whose functionality and properties arise not as inherent features of their constituent materials, but due to an artificially-engineered structure - are particularly apt for patent protection. Keltie patent attorney Emily Weal explores this exciting area of materials science and the growing body of patents protecting it.

01.04.2025

Protecting Inventions while preserving biodiversityInvesting in biodiversity conservation and research is not just environmentally responsible—it's medically strategic, as each species lost represents the permanent erasure of unique biochemical compounds that could hold the key to treating current and future diseases. Understanding biodiversity also impacts diverse fields such as animal and plant breeding, agritech and public health.

Thank you